Before Baldwin: The Crusader States and the Muslim World Around Them

If you stand in the Levant in the late 1100s—on a ridgeline above dusty roads and stony hills—you would feel history in motion. Caravans creak between cities. Pilgrims pray their way toward holy places. Fortresses glare from high ground like clenched fists. And somewhere beyond the horizon, armies are always gathering—because the land is not just land. It is memory, promise, and power.

This is the world Baldwin IV inherited: a kingdom built by crusade, surrounded by rivals, sustained by diplomacy as much as by steel. And Baldwin—teenage king, brilliant mind, failing body—would become the unlikely hinge on which the fate of Jerusalem swung.

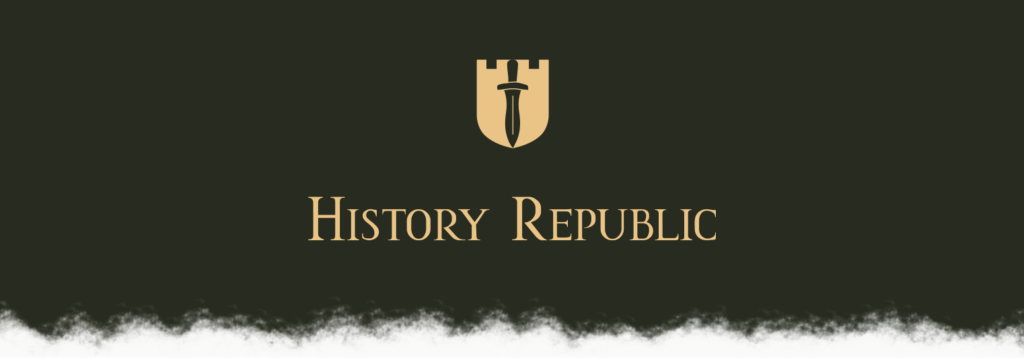

The Crusader States were not one country. They were a chain of Latin Christian realms carved out after the First Crusade captured Jerusalem in 1099. They were connected by faith and European aristocratic culture, but divided by geography, local politics, and personality.

By Baldwin’s lifetime, the major Crusader States were:

- The Kingdom of Jerusalem (the heart of the project—spiritual and political)

• The Principality of Antioch (north, wealthy, cosmopolitan, frequently unstable)

• The County of Tripoli (a coastal realm balancing trade and defense)

A fourth—Edessa—had already fallen decades earlier (1144), a warning that these states could disappear.

What made their survival possible was not that they were always militarily stronger (they weren’t), but that the region around them was often politically fragmented. Muslim power was real and formidable, yet divided across rival dynasties and competing cities.

The popular image is constant holy war—crosses versus crescents, nothing in between. The reality was messier, and in some ways more human. Yes, there were raids, sieges, crusades, counter-crusades. But there were also treaties and truces, trade, diplomacy, and local alliances—because cities still needed markets, and rulers still needed time.

And looming over Baldwin’s adolescence was one of the most consequential shifts of the medieval Middle East: the rise of Saladin

Birth, Parentage, and a Crown Waiting in the Shadows

Baldwin IV was born in 1161, into the highest stakes family in the Crusader world.

His father was Amalric I, King of Jerusalem—a hard-headed ruler who understood that survival required constant attention: alliances, fortifications, and careful pressure against Egypt when opportunities appeared.

His mother was Agnes of Courtenay, a woman later painted in extreme colors—either as a schemer or as a politically astute survivor in a court full of ambitious men. What matters most is this: she was influential, connected, and her presence in politics would remain a factor throughout Baldwin’s reign.

Baldwin was not born into peace. He was born into a kingdom that could not afford weak leadership.

Education: The Making of a Mind

Baldwin’s education was shaped by William of Tyre—a scholar, churchman, and historian who understood both theology and politics.

William did not just teach Baldwin to read and write. He taught him to think like a king: how to weigh advice, read motives in court, understand geography and logistics, and see beyond today’s skirmish to tomorrow’s alliances.

From accounts that survive, Baldwin grew into a teenager who was serious, intelligent, and unusually composed. Not cold—just aware that childhood ends early when your life is tied to a fragile throne.

But there was something else happening—quiet, invisible at first—inside his body.

The Discovery: A Boy Who Couldn’t Feel Pain

The story of Baldwin’s illness begins not in a palace chamber, but in a child’s game.

Baldwin was playing with other boys, roughhousing the way boys do—pinching, scratching, testing each other’s toughness. The other children flinched and laughed and yelped. Baldwin didn’t.

His tutor noticed something wrong: Baldwin did not react to pain in part of his body. At first it might have seemed like bravery. But bravery has limits. Nerves don’t.

Physicians were consulted. Observations followed. And slowly, the truth emerged: Baldwin had leprosy.

In the medieval world, leprosy was both medical and symbolic—a disease feared not only for what it did to flesh, but for what people believed it meant. For a prince, it implied something sharper: a kingdom without a future.

What Leprosy Meant for the Kingdom

Leprosy was progressive. It could begin with numbness and patches on the skin, then advance into nerve damage, deformities, infections, and disability. In an age without modern antibiotics, complications could be brutal.

For Jerusalem, Baldwin’s diagnosis created a political earthquake:

- Succession anxiety: Could he marry? Could he produce heirs?

- Military fear: Could he ride, fight, command?

- Legitimacy questions: Would nobles accept a king whose body was failing?

- Foreign opportunism: Would enemies strike once his weakness was known?

The court’s first instinct was to manage the information—to keep it quiet, to buy time. Baldwin himself, however, could not be hidden from destiny forever. The disease moved as it pleased.

Treatment and Daily Reality: Faith, Medicine, and Endurance

Treatments for leprosy in the 12th century were limited and inconsistent. They could include ointments and salves, dietary restrictions, baths and herbal remedies, and prayer and pilgrimage (often intertwined with medicine). None of it stopped the disease.

So Baldwin’s “treatment” became something else: adaptation. He learned to live with numbness, weakness, and the slow theft of control from his own body. And as he aged, he learned something even harder: he could not defeat leprosy—but he could refuse to let it defeat his kingship.

A Child King: How Baldwin Rose to the Throne

In 1174, Amalric I died. Baldwin was around 13 years old.

Jerusalem needed a king. It got a boy.

A regency was necessary at first, because of Baldwin’s age. The leading figure in this early period was Raymond III of Tripoli, an experienced noble with influence and resources—exactly the kind of man you want near the throne when an enemy is watching for weakness.

As Baldwin grew older, he asserted himself. He listened, learned, and then began to rule—not as a symbol, but as a decision-maker. He did so while the most dangerous opponent of the Crusader States was rising to the south and east.

Saladin’s World: Unity as a Weapon

Saladin did not begin as “Saladin the Great.” He rose through military and political skill, and he understood that the Crusader States survived partly because Muslim leadership was divided.

His long-term strategy was to change that. He consolidated power in Egypt, strengthened his position in Syria, and built a coalition that could sustain major campaigns. His reputation grew with each success—not only as a commander, but as a ruler with a mission: to reclaim Jerusalem.

Baldwin understood what this meant. The question was not if Saladin would test Jerusalem. It was when.

The Road to Montgisard

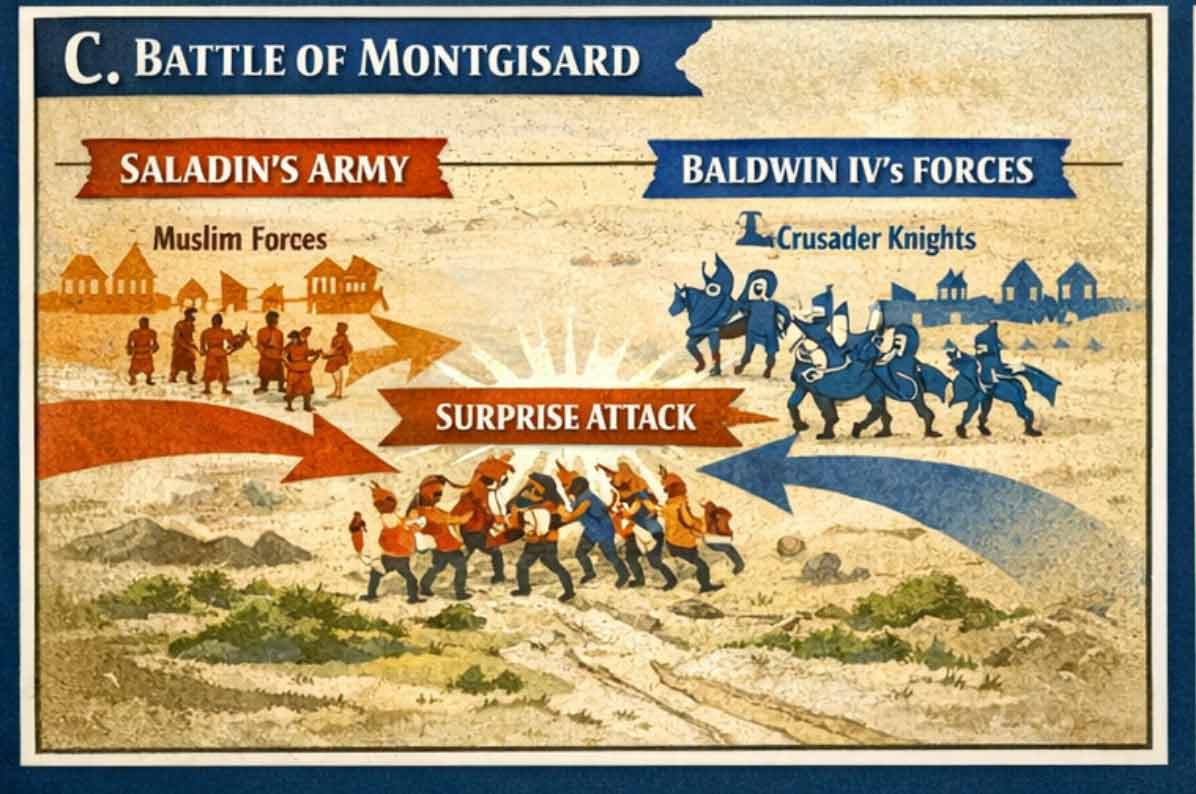

In 1177, Saladin launched a major invasion into the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s territory. He expected to overwhelm it.

Baldwin was young and known to be ill. The kingdom had internal factional tensions. Saladin’s forces were larger and had momentum. A decisive victory could shatter the Latin presence in the region.

For Saladin, it was a calculated move. For Baldwin, it was a crisis—and an opening.

Montgisard: A Miracle Made of Decisions

The numbers were against Baldwin. Saladin’s army was far larger.

But medieval warfare is not a spreadsheet. It is fear, dust, terrain, morale, and moments.

Baldwin moved quickly with what he could gather—knights, infantry, and the kind of desperate courage that forms when you know you can’t afford to lose. Near Montgisard (often associated with the area near Ramla), Baldwin’s forces struck hard with a concentrated attack when Saladin’s army was extended and vulnerable.

Saladin’s army broke—scattered, chased, bloodied, and forced into urgent escape. Saladin himself narrowly avoided capture.

Why Montgisard Mattered

Montgisard mattered for three reasons:

- Psychology: It proved Jerusalem was not helpless, even under a sick boy king.

- Politics: It strengthened Baldwin’s authority and legitimacy.

- Strategy: It bought time—time to fortify, negotiate, and prepare for the next wave.

Victories do not always change history by what they conquer. Sometimes they change history by what they delay. Montgisard delayed disaster.

Aftermath: Victory, Then Reality

After Montgisard, Baldwin was celebrated. The image of the young king—ill, determined, present—became powerful.

But Baldwin was not naive. He understood Saladin would learn, adapt, and return stronger. And Baldwin’s body was still betraying him.

So Baldwin turned increasingly toward the most difficult task of all: holding the kingdom together from the inside.

Baldwin and Saladin: Enemies With a Strange Respect

Baldwin IV and Saladin fought each other in war and maneuvered against each other in diplomacy. Their relationship was not friendship, but it was not cartoonish hatred either.

They represented two different visions of the region’s future, and both understood the gravity of what they were doing. Over time, Saladin came to respect Baldwin’s resilience. Baldwin, in turn, recognized Saladin’s intelligence and patience.

For a time—because of Baldwin’s leadership—neither could fully crush the other.

The Court: Factions, Marriages, and the Poison of Succession Politics

If battlefield danger was obvious, court danger was subtle—and sometimes worse.

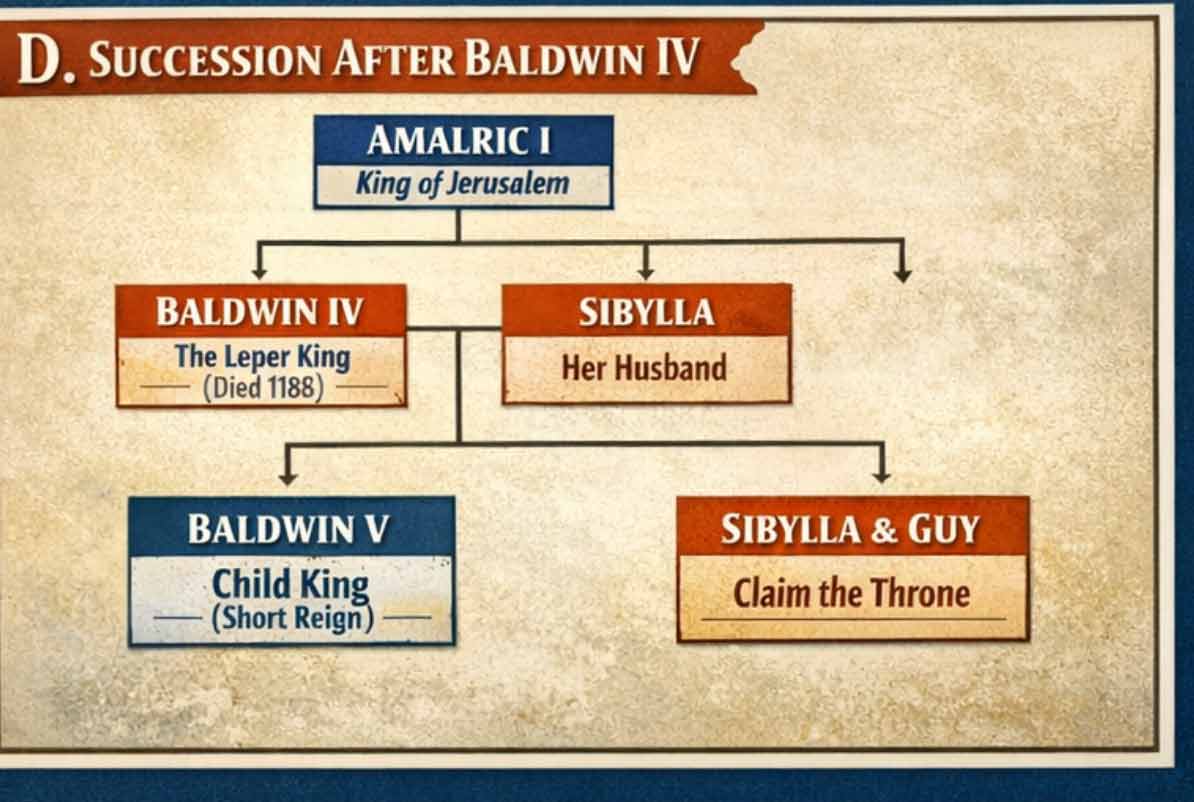

Baldwin could not rely on producing an heir. That meant succession had to come through his family line, especially his sister Sibylla and her child. This opened the door to factional conflict: nobles jockeying to control the next king, marriages arranged like alliances, and rival power blocs forming around different candidates.

One of the most controversial figures to emerge was Guy of Lusignan, who became Sibylla’s husband and, by extension, a potential future ruler. Baldwin came to distrust Guy’s judgment and leadership. In a kingdom where one bad decision could mean annihilation, that distrust mattered.

Regencies: When the King Couldn’t Always Physically Rule

As Baldwin’s leprosy advanced, he increasingly required assistance—not always because his mind failed, but because his body did.

Regents and senior nobles took on larger roles at different moments. This wasn’t one neat “regency period,” but a shifting reality: Baldwin remained king and remained decisive, yet he increasingly relied on others for execution.

To secure the future, Baldwin arranged for his young nephew, Baldwin V, to be recognized as successor—placing the future of the kingdom in the hands of a child in order to block the wrong adults from seizing control too soon.

Death: The Kingdom Loses Its Anchor

Baldwin IV died in 1185, still in his early twenties. He had ruled for roughly a decade—an astonishing span given his condition and the constant danger surrounding Jerusalem.

His death was not just a personal tragedy. It was a strategic turning point. Baldwin was a stabilizing force—a mind that could balance factions, assess threats, and resist impulsive choices. Without him, the kingdom’s internal divisions became more lethal.

Aftermath: Succession and the Slide Toward Catastrophe

After Baldwin IV, the crown passed to Baldwin V, the child successor Baldwin had elevated. But Baldwin V did not live long. The kingdom soon fell back into the gravitational pull of factional politics—the very thing Baldwin had tried to manage.

Within a short period, the region saw one of the most decisive disasters in Crusader history: the defeat at Hattin (1187) and the loss of Jerusalem soon after. Many historians believe Baldwin IV was the last king of Jerusalem able to hold the realm together under pressure.

Legacy: The King Who Refused to Be Reduced

Baldwin IV is remembered not for conquest or empire, but for holding the line.

He ruled while dying. He led while disabled. He made hard political choices in a kingdom that could not afford sentiment. His legacy is a reminder that leadership is not measured only in victories, but in endurance—especially when endurance is all you have left.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem eventually fell. But Baldwin’s story survives because it touches something older than borders: a young person given an impossible job, a body that fails, a duty that does not—and a refusal to quit.