Picture Eastern Europe in the early tenth century: vast forests of birch and pine, labyrinthine rivers gleaming under northern light, and trade routes that wrapped the known world together like the strands of a woven net.

From the Baltic Sea southward along the Neva, Volkhov, and Dnieper, Scandinavian longships—sleek, dragon‑prowed, and shallow‑keeled—glided beneath cloud‑white sails.

Their crews, the Varangians (Vikings of the East), sought more than plunder. They wanted markets. Furs from the north, honey from the steppe, wax, and slaves—all flowed south to Constantinople (Byzantium), returning north as silks, silver dirhams, and Byzantine icons.

Politically, this enormous inland maritime world lacked a single overlord. Slavic farm villages, Finno‑Ugric forest hunters, Turkic steppe nomads, Khazar tax collectors, and Norse adventurers formed a volatile mosaic of alliances, tribute systems, and vendettas.

Towns such as Novgorod, Smolensk, and Kyiv served simultaneously as fortified emporia, clan strongholds, and embryonic city‑states. Into this world strode a series of charismatic rulers who traced their lineage to a Varangian chieftain named Rurik.

His successors consolidated the Kievan Rus polity—part kingdom, part trading company, part Viking warband.

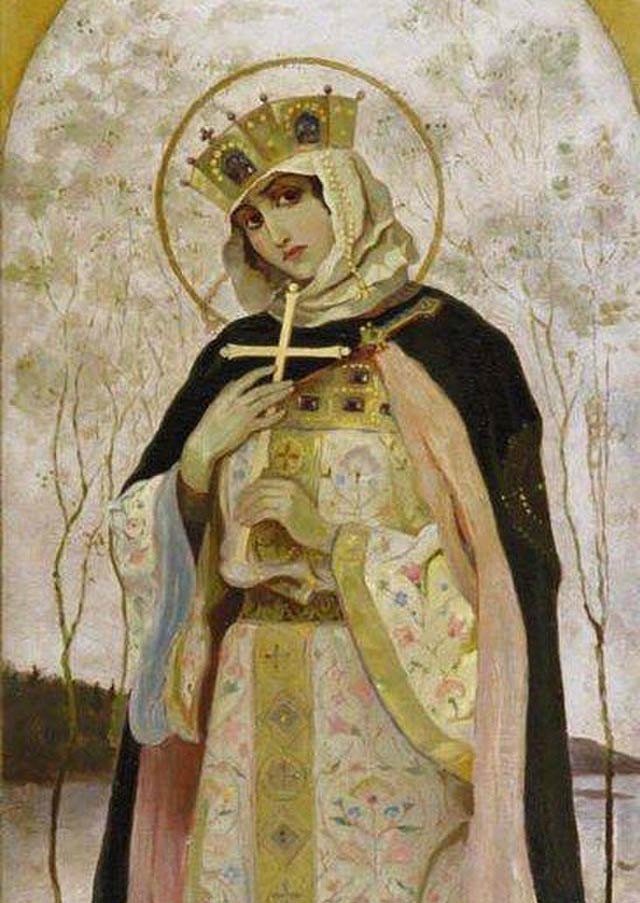

Amid the clash of axes and treaty oaths, a single woman would reshape the Rus realm far beyond what any raider or prince managed: Olga, later canonized Saint Olga of Kyiv.

Her story arcs from the quiet backwaters of Pskov to the golden halls of Constantinople, spanning revenge sagas worthy of the Iliad and diplomatic coups that prefigured medieval statecraft.

Beneath the legend of flaming birds and buried envoys lies a deft political mind that turned a fragile trading confederation into a budding principality.

Origins beside the Velikaya River

Our primary window into Olga’s early life is the Primary Chronicle (Povest Vremennykh Let), a compilation of oral tales and monastic notes written roughly two centuries after her death. According to its pages, Olga was born between 890 and 905 CE, “in the land of Pskov.” At that time Pskov was not yet the stone‑walled medieval city we envision today, but a wooden riverside settlement ringed by stockades, perched near portages connecting Baltic trade to the upper Dnieper route.

Olga’s father—whose name the Chronicle does not preserve—was likely a ferryman. This profession sat at the nexus of commerce: ferry captains transported merchants, their goods, and sometimes entire longships across river bends too treacherous for rowing.

Ferrymen dealt in silver coin and rumor: which clan was at war, what furs fetched highest price, whether raiders prowled downstream.

Growing up amid this flow of goods and stories, young Olga absorbed more than rowing techniques; she learned the unspoken laws of barter and hospitality, the importance of measured words in negotiations, and the dangers of appearing weak in a world where weakness invited raids.

No physical descriptions survive, yet medieval chroniclers lauded her “beauty of visage” and “acumen surpassing her sex.” Such compliments, though cliché, hint at a woman who commanded attention through appearance and intellect.

She probably spoke the local Slavic dialect, understood the Norse of visiting Varangians, and knew the barter‑patois of Finno‑Ugric woodsmen. These linguistic threads would later form the tapestry of her political life.

Igor and the Rurikid Inheritance

Olga’s path changed course the day Prince Igor—Rurik’s successor—arrived at the ferry, according to legend around 903 CE.

Details vary: Legend tells that Prince Igor, heir to the fledgling Rurikid dynasty ruling Kyiv, became separated from his retinue while hunting and sought passage across the river.

The young ferryman’s daughter coolly refused his flirtatious banter, insisting on fair payment and decorum. Impressed by her self‑possession, Igor remembered the encounter.

Years later, after securing his position in Kyiv, he returned to Pskov to claim Olga as his wife. Whether every detail is true or courtly embroidery, the story foreshadows a defining trait of Olga’s life: she negotiated from a position of fierce self‑respect in a world that underestimated her.

Igor needed allies in the north to secure trade arteries feeding Kyiv. By choosing a bride from Pskov, he signaled goodwill to the northern clans and gained a partner untainted by rival Varangian ambitions.

Igor’s political landscape was turbulent. After Rurik’s death (c. 879 CE), Varangian warrior‑prince Oleg the Seer ruled as regent for the young Igor, capturing Kyiv in 882, slaying its previous rulers, and transforming the hilltop settlement into the Rus capital.

Oleg’s reign blended trade diplomacy with ferocious raids. When he died, perhaps struck by a serpent in Norse saga style, Igor inherited both throne and task: maintaining the fragile chain linking northern Novgorod to southern Kyiv, while extracting tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes without sparking mass revolt.

Marriage, Motherhood, and Courtly Lessons

Between 910 and 915 CE—scholars disagree on the exact date—Igor married Olga. The Chronicle immediately lauds her wisdom: “She served as counselor to her husband.” Yet daily life for a Rus princess was anything but idle.

Court at Kyiv oscillated between pagan rituals—sacrificing horses to Perun, the thunder god—and pragmatic commerce deals hammered out with Arab merchants. Olga learned to oversee household slaves, balance tribute accounts, and host feasts where Nordic skaldic verse met Slavic folk songs.

Around 942 CE she bore Svyatoslav, the dynastic heir. The Chronicle notes no other children, though later genealogies claim daughters whose names vanished from records.

Olga’s motherhood coincided with Kyiv’s transformation into a cosmopolitan river port: Byzantine traders bartered silk, Khazar envoys sought revenue shares, and Frisian adventurers peddled swords.

This kaleidoscope forged Olga’s later inclusive policies—but first, tragedy would force her onto the throne.

The Fatal Tribute: Igor’s Murder

In the winter of 945 CE, Igor embarked on a routine collection tour among the Drevlians, a Slavic tribe inhabiting dense oak forests west of Kyiv.

Contemporary Arab geographer Al‑Masʿūdī labels the Rus tribute “taxes taken by the sword,” and so it was—Varangians arriving with axes and demands.

The Drevlians resented Varangian overlordship but usually paid up. This time Igor demanded more than the customary tribute—some chroniclers say he returned after the first payment “with a small escort” to squeeze a second levy.

Outraged, the Drevlian prince Malk (or Mal) urged rebellion and ambushed Igor’s party near modern Iskorosten, and killed him. The Chronicle’s grisly detail—tying him to bent birch trees and tearing him apart—may be literary flourish, yet his death was certain.

Kyiv reeled. Varangians prized strength; a prince slain by vassals signaled vulnerability. The three‑year‑old heir could not rally troops.

Olga, now a widow in her mid‑thirty‑something prime, confronted a potentially fatal trifecta: a child successor, greedy nobles circling for power, and triumphant Drevlians sending marriage proposals.

Seizing Regency and Vengeance

Ordinarily a Varangian widow might retreat behind timber palisades until a male relative assumed guardianship. Olga did the opposite. She summoned Kyiv’s nobility, invoked Igor’s blood, and demanded regency on behalf of Svyatoslav.

Many nobles—especially Slavic clans wary of unchecked Varangian swashbuckling—saw in her a stabilizer. They affirmed her rule. Yet outside Kyiv, the Drevlians plotted to cement dominance by wedding Prince Malk to Olga, thereby legitimizing revolt.

Turning the Tables: Act I—The Bathhouse

When Drevlian envoys arrived in Kyiv proposing marriage, Olga welcomed them with apparent cordiality. She invited them to “freshen themselves” in a bathhouse—an honor, since baths held ritual significance among Slavs and Norse alike.

As they soaked, attendants barred doors and set the structure aflame. The envoys’ screams rose above crackling timber; ashes dusted the spring air. She sent word to Malk: “Your messengers were honored.”

Act II—The Pit of Earth

Unaware of their comrades’ fate, a second Drevlian embassy arrived. Unsuspecting, the Drevlians sent distinguished elders. Olga greeted them from the palace gate, offering a grand feast.

First, she said, Kyivans would carry them in a koromyslo (palanquin) upon shoulders “so all may honor you.” The procession halted at the courtyard where a trench waited. Bearers dumped the dignitaries in; dirt rained down. “Is this honor to your taste?” Olga reportedly taunted.

Act III—The Mead Massacre

Next, Olga announced she would hold a funeral banquet at the Drevlian capital of Iskorosten (modern Korosten) to weep over Igor’s tomb. Hundreds of Drevlians gathered; barrels of mead flowed. When the guests were deep in drink, Olga’s warriors fell upon them, killing perhaps 5,000, the Chronicle claims, though numbers likely inflated.

Act IV—The Fiery Birds

Iskorosten still stood. Olga besieged it unsuccessfully—wooden walls repelled scaling ladders. She then offered mercy: if each household gifted three pigeons and three sparrows, she would withdraw. Relieved, townsfolk complied. Olga’s men tied smoldering sulfur‑soaked cloth to bird legs and released them. The birds returned to nests under thatched eaves—the city ignited from within. When defenders fled the flames, Olga’s troops captured them, executing leaders and enslaving survivors.

Folklorists debate the plausibility of combustion‑carrier pigeons, yet archaeological layers at Korosten show mid‑10th‑century burning. Regardless, Olga’s vengeance achieved its purpose: it obliterated Drevlian autonomy and broadcast her ruthlessness. In the volatile steppe world, reputation equaled deterrence.

Laying Foundations of a State

With Drevlian resistance crushed, Olga focused on governance. Her regency lasted roughly 19 years (945‑964 CE), overlapping Svyatoslav’s adolescence. During this time she moved Rus from seasonal tribute raiding toward proto‑feudal administration.

Creation of Pogosti

Olga toured her realm, marking sites for pogosti—fortified administrative centers where tributes were collected and justice dispensed. Typically located near river confluences for transport access, each pogost included storehouses, barracks, and often a church after her conversion.

By setting fixed tribute quotas and collection dates, she curtailed the arbitrary looting that had provoked Drevlian rebellion. In effect, she replaced Viking danegeld chaos with early tax districts—an embryonic bureaucracy.

Reorganization of the Druzhina

The Varangian druzhina (prince’s retinue) formed Rus military muscle but also drained royal coffers with lavish gift expectations. Olga retained elite Varangians for foreign campaigns yet cultivated Slavic boyars (nobles) for local administration, splitting power bases and reducing any single faction’s leverage against the throne.

Trade and Coinage

Silver dirhams from Islamic Caliphates flooded Rus markets via the Volga route. Olga standardized weights and measures at pogosti, likely issuing stamped lead weights bearing runic or Slavic marks. While no Olga‑minted coin survives, excavations show a spike in hacked silver (“hacksilver”) hoards tagged to her regency—a sign of vibrant regulated trade.

Olga of Kyiv Converts to Christianity

Olga recognized that long‑term stability required an ideological counterweight to pagan warlord culture. Christianity, spreading slowly via Greek clergy and Balkan captives, offered not just spiritual comfort but diplomatic currency. In 957 CE, Olga embarked on a voyage to Constantinople—capital of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine Pageantry

Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus—scholar, statesman, and ceremonialist—documented her arrival. Byzantine protocol dazzled foreign dignitaries with gold mosaics, mechanical lions roaring in the palatial Magnaura, and processions of silk‑robed officials. Olga, however, met the spectacle with poise. Constantine’s own treatise De Cerimoniis remarks on her dignity and intelligence—rare compliments in a text that often belittled barbarians.

Baptism and the Name Helena

During her stay, Olga accepted baptism, taking the Christian name Helena—likely sponsored by Constantine or his Empress. The emperor served as godfather, forging fictive kinship. Baptism rites in the Hagia Sophia submerged her in a white‑marble font, anointed her with chrism, and clothed her in linen.

Candle‑lit choirs intoned Greek hymns as incense swirled from golden censers. For Olga, the ceremony was not merely religious but geopolitical theater: it signaled Rus entry into Christian diplomatic networks.

Diplomacy’s Limits

Olga requested a Byzantine bishop and priests to accompany her home and help convert her people. Constantine, cautious, obliged. Baptism conferred spiritual kinship, but Constantine refused to marry Olga (now technically his “spiritual daughter”) to any Byzantine noble, stalling her hopes for a dynastic alliance.

Overtures to the Latin West

Olga hedged her bets by engaging the Western Church. In 959 CE she sent envoys to Holy Roman Emperor Otto I seeking priests “to teach her people.” Otto, building his own Christian prestige, dispatched Bishop Adalbert of Magdeburg with clergy.

Yet upon reaching Rus borders in 962, Adalbert met resistance—Svyatoslav, co‑ruler and a vowed pagan warrior, barred Latin clergy from Kyiv.

Adalbert returned in frustration. Although the mission failed, Olga’s outreach underscores her diplomatic agility—she could play Constantinople against Latin Christendom for Rus benefit.

Svyatoslav: The Warrior Son

By the mid‑960s, Svyatoslav was old enough to rule. He shared his father Igor’s martial bent but exceeded it in ambition. Chroniclers depict him shaving his head save for a single lock (a steppe warrior style), wearing one gold earring, and sleeping without a tent or stove. His campaigns were relentless:

- Volga Bulgars — Defeated in 965, opening trade beyond the Volga bend.

- Khazar Khaganate — Sacked capital Atil circa 968, breaking a centuries‑old steppe power.

- Balkan Wars — At Byzantine behest he invaded Bulgaria but soon threatened Constantinople itself.

Svyatoslav’s zeal alarmed Olga, who managed Kyiv’s domestic realm. She admonished him to winter in Kyiv to deter Pecheneg nomads, but he preferred campaigning.

When Pechenegs besieged Kyiv in 968, Olga—ill but resolute—took command. She dispatched messengers through enemy lines to summon Svyatoslav, organized grain distribution, and rallied defenders atop the city ramparts. Upon his return and the siege’s lifting, she scolded him: “You should think of home, not always war.”

The Last Days of the Regent

Olga’s health deteriorated in spring 969 CE. Monks tended her in a wooden palace on Kyiv’s hill, where she requested Christian prayers rather than pagan rites. She called Svyatoslav, asked him to protect her grandsons, and repeated her plea for him to remain in Kyiv. He agreed, but his restless nature chafed.

On 11 July 969, Olga died. The Chronicle records: “They carried her forth and lamented her greatly, her son and grandsons, and all the people.” Her funeral—unprecedented in Rus—followed Christian customs: a procession bearing icons, priests chanting Greek and Slavonic hymns, incense wafting over the Dnieper cliffs.

She was entombed in a stone sarcophagus, possibly at the Church of the Holy Wisdom (a precursor to later cathedrals). Pagan Rus nobles attended, curious yet respectful, for Olga commanded loyalty that transcended faith lines.

Svyatoslav, true to his nature, departed soon after, campaigning against Byzantium. Olga’s prophecy of peril proved accurate: in 972 Pechenegs ambushed Svyatoslav at the Dnieper rapids and, legend says, fashioned his skull into a jeweled drinking cup—custom among steppe warriors.

Turmoil and Christian Triumph

Olga’s passing reopened power struggles. Her grandsons—Yaropolk, Oleg, and Vladimir—each claimed portions of Rus. Yaropolk (Kyiv) and Oleg (Drevlians) soon fought, resulting in Oleg’s death. Vladimir, ruling Novgorod, fled to Scandinavia, returned with Varangian mercenaries, and seized Kyiv in 980 CE.

Though Vladimir initially upheld pagan traditions, seeds planted by Olga germinated. Seeking legitimacy and trade leverage, Vladimir evaluated faiths—Islam, Judaism, Western Christianity, and Byzantine Orthodoxy.

Chronicles credit emissaries returning from Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia, echoing Olga’s awe, saying, “We knew not whether we were in heaven or earth.”

In 988 CE, Vladimir accepted Orthodox baptism, married Byzantine princess Anna Porphyrogenita, and baptized Rus. He later dug up Olga’s remains, re‑burying them with honor in the newly built Desyatinnaya Church(Church of the Tithes).

Church writers dubbed Olga “Isapostolos”—equal to the apostles—for beginning Rus’s path to Orthodoxy. Her revenge tales became a moral example: righteous wrath tempered by eventual enlightenment.

Olga of Kyiv’s Legacy

Administrative Genius

Olga’s pogosti system survived centuries, evolving into uyezds (districts) under later principalities and informing Muscovite tax structures. By formalizing tribute, she shifted Rus from predatory raiding to sustainable revenue—crucial for urban growth.

Diplomatic Trailblazer

She harnessed Christianity not merely as faith but as diplomatic language, negotiating on near‑equal terms with Byzantium and the Holy Roman Empire. Her ability to charm the scholarly Emperor Constantine—who rarely praised foreigners—attests to her acumen.

Cultural Synthesis

Olga straddled pagan and Christian, Varangian and Slavic, northern woods and southern steppe. Her court patronized craftsmen forging Norse zoomorphic brooches alongside Byzantine enamel icons. This syncretism incubated a distinct Rus culture later expressed in illuminated manuscripts and cathedral art.

Feminine Authority

Few medieval women wielded solo power in Eastern Europe. Olga’s regency defied norms, showing that strategic ruthlessness and administrative talent could outweigh gender prejudice. Later Russian chronicles cite her as the archetype of wise matron counsel to wayward sons.

Sanctity and Contested Memory

Canonized around 1240, her sainthood was reaffirmed by both Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox Churches. Each national narrative highlights different facets: Russians emphasize unifying statecraft; Ukrainians, the early autonomy of Kyivan rule; feminist historians, her agency; military analysts, her psychological warfare.

Epilogue — The Echo of Flaming Birds

On warm July evenings in modern Kyiv, the golden domes of St. Michael’s Monastery catch the sunset’s last fire. Near its square stands a statue grouping: Saint Andrew the Apostle flanked by Saints Cyril and Methodius, with Saint Olga raising a cross before them—matriarch of Rus Christianity.

Few passersby recall the ferryman’s daughter of Pskov or the pigeons that blazed through Drevlian skies, yet Olga’s spirit permeates the stones.

Her reign was a pivot between eras: the twilight of Norse adventurism and dawn of Slavic statehood; the hush before Christian chants replaced pagan drumbeats; the handover from retaliatory raids to codified taxes and foreign treaties.

She wielded cruelty when survival demanded, yet sought faith when vision called. Lest we judge too quickly, the tenth century granted no gentle paths to sovereignty.

Every time archaeologists unearth dirham hoards along the Dnieper or Byzantine crosses amid Norse grave goods, they find echoes of the regent who welded disparate worlds into a single trajectory.

In the saga of nations, some leaders conquer territories; Olga conquered time, ensuring that her grandson, her city, and her church would stand long after the birch trees bent silently back into place along forgotten forest glades.

If the wings of her fire‑bearing pigeons still flutter in Slavic folklore, they also fan the embers of a deeper truth: that visionary leadership can rise from the humblest ferry crossing and blaze a path into history’s firmament.